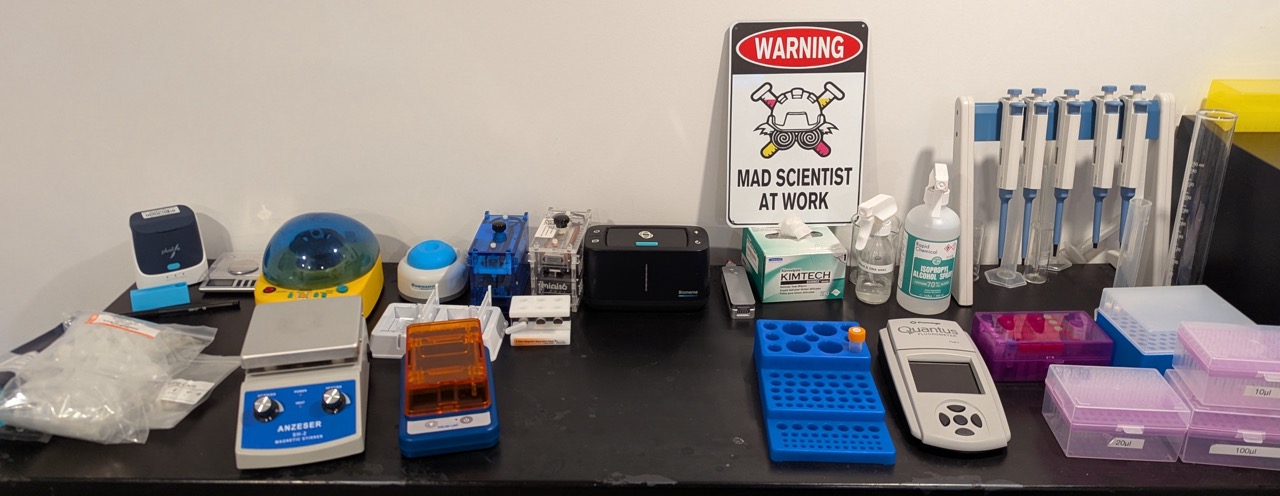

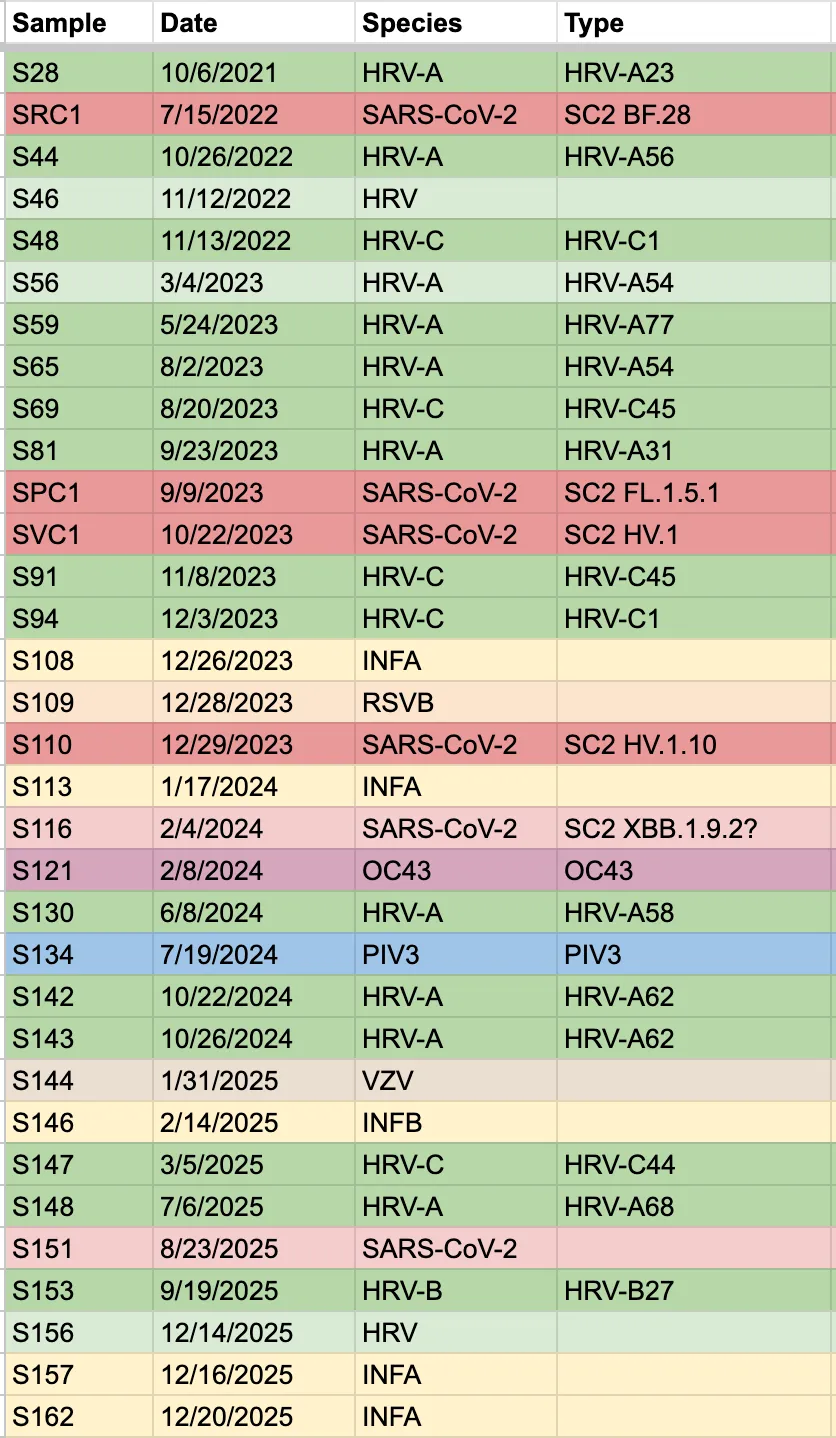

Over the past 6 years I have spent around $45,000 USD in order to do 300+ experiments on the viruses moving through my household. When people ask me why on earth I would spend so much time and money on a home lab, I usually just answer “because I’m curious” or “for fun”. But after years of running PCR assays whenever someone in the house has a cold, I can finally say that it is sometimes actually useful … while remaining wildly impractical of course.

I am confident that, in the future, home molecular testing for common pathogens will be as simple, cheap, and uncontroversial as home blood sugar testing is today, revolutionizing our approach to public health and personal medicine. In this essay I will give some background on home virus testing and share a few examples of how having a molecular virology lab in my home has benefited my family.

Background

Historical context

In learning about the history of public health, I’m struck by the repeated stories of people accepting unnecessary suffering due to self-inflicted ignorance long past the point of scientific discovery. For example:

- John Snow struggling to get the Broad St. pump handle removed to stop people from drinking water contaminated by cholera-ridden sewage when the prevailing belief was that disease was spread by “bad air”.

- Women dying because doctors refused to wash their hands between autopsies and delivering babies.

- The nearly century-long refusal to fully appreciate that respiratory viruses are spread predominantly through inhalation of aerosols rather than through contact and droplets.

It seems that in public health, there is a gulf between knowledge and understanding. 20 years from now, which of our ignorances around respiratory infections will we look back on and shake our heads at? Are we now at the beginning of a new movement which will revolutionize our approach to respiratory disease the way the sanitary movement did for waterborne pathogens?

The state of home virus testing

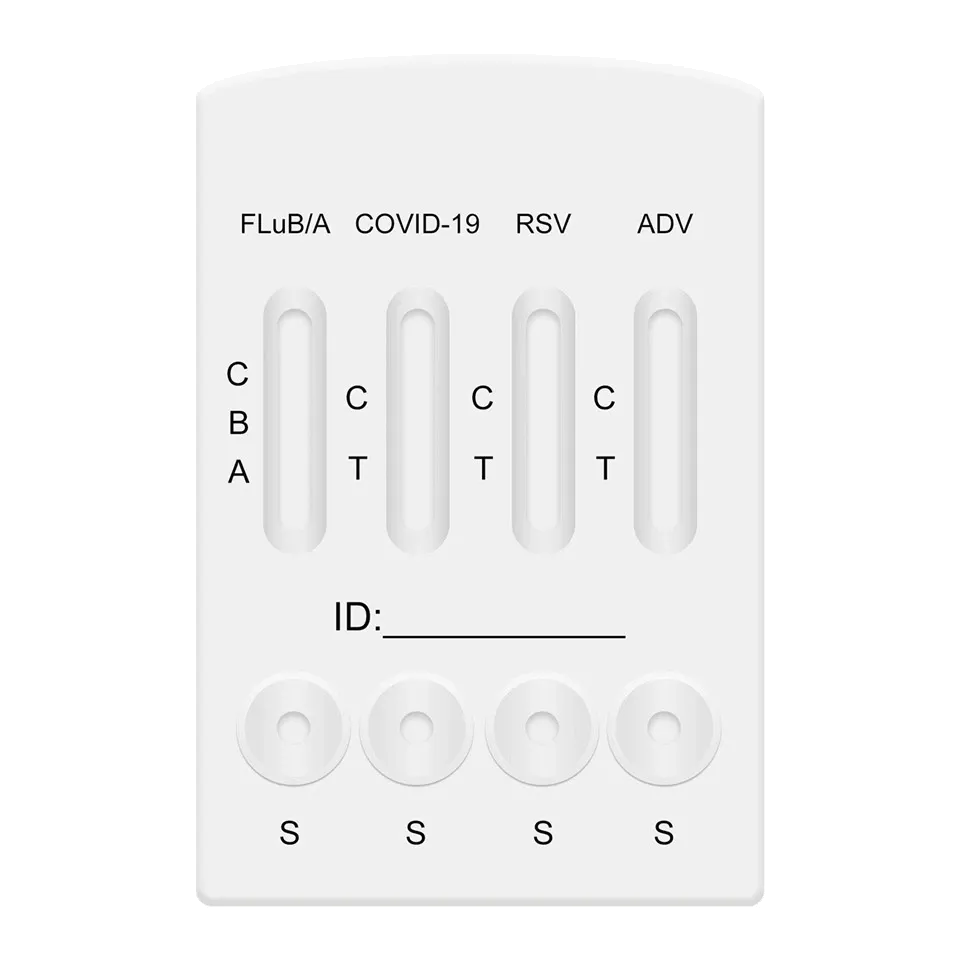

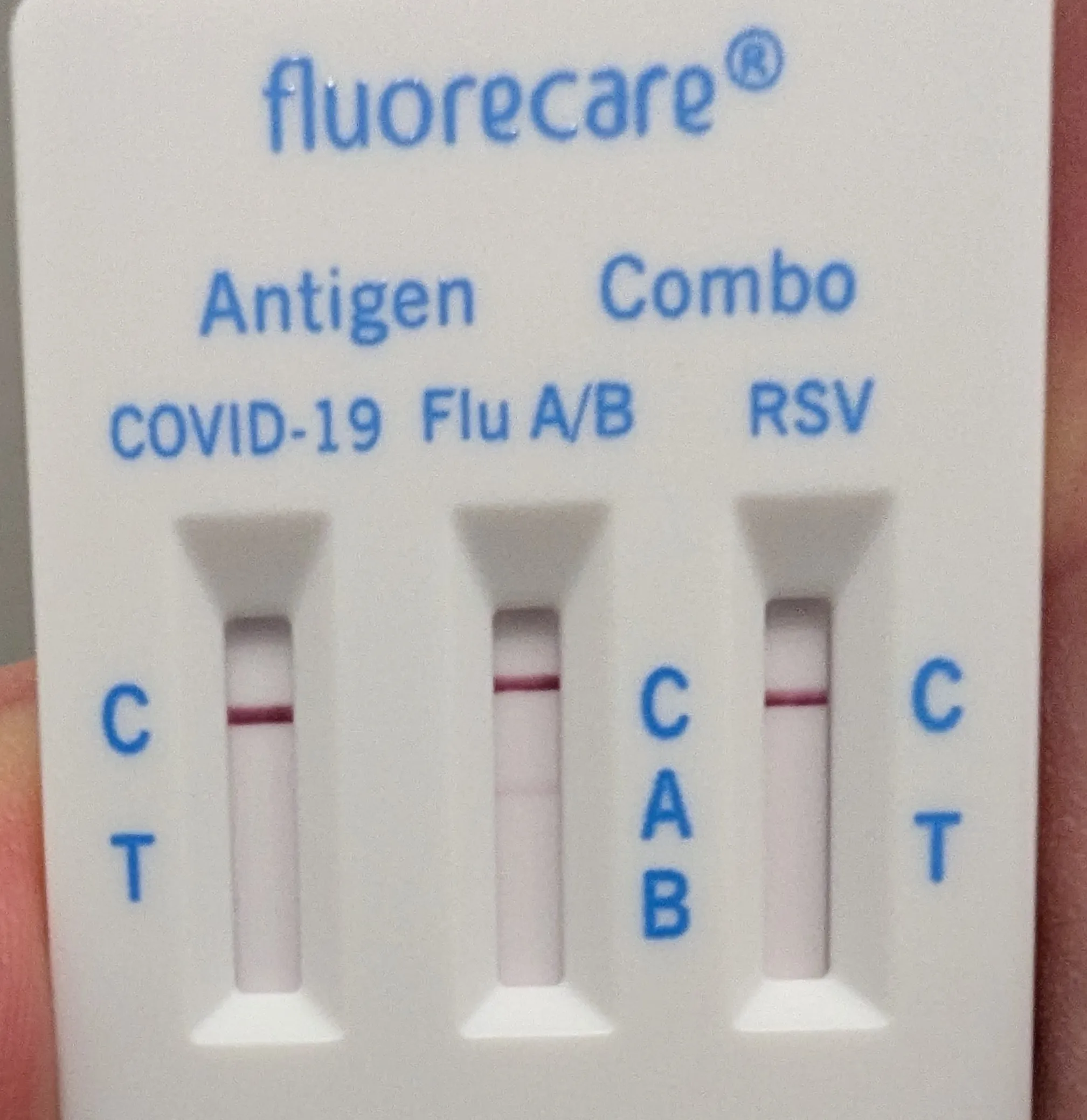

In 2020 I predicted that molecular virus testing would become common in the home. Of course, I failed to predict that rapid antigen lateral flow tests would largely fill this role for COVID-19. Antigen tests are cheap, fast and easy to use. While not nearly as sensitive as molecular tests, for most people looking to reduce transmission risk, antigen tests are the practical way to go. There are now also combination antigen tests on the market which allow you to test for COVID-19 as well as a few other common respiratory viruses like Influenza A & B, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), and Adenovirus.

Molecular tests have a few big advantages over antigen tests. First, they are sensitive enough to detect an infection around a day before really becoming contagious. Personally, I avoided infecting a number of friends with COVID-19 thanks to the sensitivity of home molecular testing. Antigen tests also tend to have a small (~0.2%) risk of false positives, which can be quite annoying if you don’t have an easy way to verify the result with a molecular test.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, two main home molecular tests were widely available (at least in North America), the Lucira Check-It and later the Cue test, running around $55 - $75 USD per test. Unfortunately after a fast rise and IPO, both companies struggled (unfairly, in my opinion) with regulatory approvals and ultimately went bankrupt.

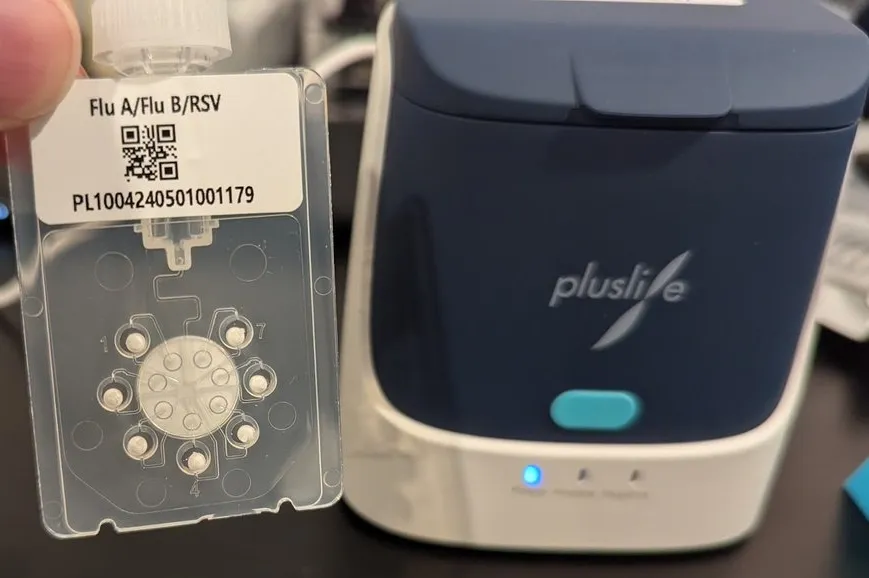

Since then the Chinese Pluslife device (with it’s awesome 3rd party web app virus.sucks) has become popular, with a substantial online community of fans. At around $8/test these are the most cost-effective molecular tests available to consumers. Unfortunately they are not approved in North America and have gotten more difficult to import here. Metrix is a new $25/test molecular testing system on the market in the US which looks similar to Cue, but I haven’t used it myself yet.

These home molecular tests are a great complement to antigen tests for predicting future contagiousness and for defending against antigen false positives. Personally I run a Pluslife test whenever I want a quick test for COVID-19 or Influenza. But they are not nearly as powerful as what can be done with a full molecular virology lab.

Advantages of having a molecular biology lab

The biggest limitation of home tests is that they don’t test for the most common cause of the common cold, Rhinovirus. Rhinovirus is incredibly diverse and so particularly difficult to design a simple reliable test for. When someone is sick in my house I typically check it against 15 different viruses, and more often than not it’s Rhinovirus that I find. In my experience it’s much more powerful and satisfying to reliably be able to answer the question “what do I have” instead of simply confirming “it’s not COVID or Flu”.

A molecular virology lab can also provide additional details, such as:

- Viral load: how much virus is present

- Variant analysis: are two samples definitely different

- Genotyping: which exact strain of a virus is present

Anecdotes from my household

My primary goal with my lab is to deeply understand how widespread virus testing may contribute to improved infection control and a sense of personal empowerment over our own health. Below are a few anecdotes from how I’ve found my lab to be useful towards those goals.

But first I want to acknowledge that there are some risks to what I’m doing. All of my equipment and reagents are “for research use only”, meaning they are not suitable for medical use. I am certainly not qualified to be giving medical diagnoses or medical advice. We have medical testing regulations in order to protect people from unreliable products which can cause harm including a false sense of confidence and a poor substitute for seeking proper healthcare advice. I do not sell testing or otherwise broadly test people outside my family. I am careful to explain to my family that my results are unreliable and may represent false positives, or false negatives. I am careful not to increase transmission risk in any way, and all of my samples are inactivated (killed) so that they are not infectious and so do not fall under any biosafety regulations. I do not propagate virus or grow bacteria in my lab, I do not buy dangerously toxic or carcinogenic reagents, and I dispose of all waste in accordance with local regulations. I am not encouraging anyone else to do what I am doing and I can’t offer advice on any legal implications.

With that out of the way, let’s get to the fun stuff!

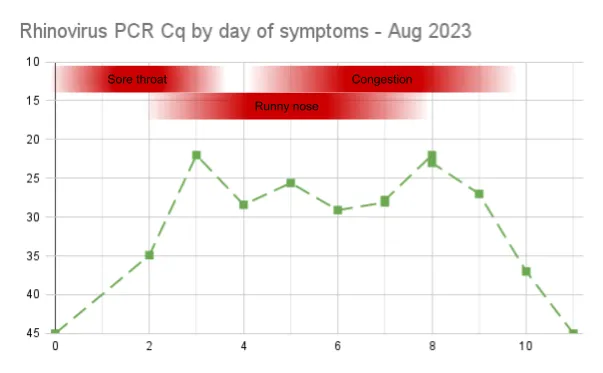

Making quantified risk-benefit tradeoffs

The first question I always have when I have a cold is “what do I need to do to avoid spreading this”. Within our household we generally isolate from eachother when we are sick, relying on masking and good ventilation with UV-C HVAC sterilization to prevent colds spreading to eachother. This was particularly important before my son moved out to University because a cold would typically knock him on his back for 1-2 weeks, causing him to miss school and exams. Before I had a good testing protocol figured out, we had a couple cases where someone in the family said “I feel mostly better”, stopped isolating, and then a few days later others in the house got sick. For Rhinovirus I’ve found that symptoms do generally correlate pretty well with viral load (amount of virus in a swab), but it tends not to be until I’m feeling perfectly better (no congestion at all) that the virus drops to a point where it’s unlikely to be contagious. For example, here is a plot of the viral load each day for a Rhinovirus I had in August 2023.

Before building up my lab, I’d say we had about a 50/50 chance of catching eachother’s colds in the house. With the availability of rapid antigen tests for COVID and Flu, we have had a powerful tool to help decide when to stop isolating (eg. 2 negative tests 48 hours apart). But when someone has just a cold, for which no antigen tests exist, I run PCR tests to help decide when to stop isolating. This has worked very well, with almost no secondary infections in the household.

My own behavior has also changed. In the past I’d work from home when feeling sick, but typically go back to the office once I “felt better” and could tell myself “I’m probably not contagious”. Now that I can get data instead of guessing, I continue working from home and isolating from my family for an extra day or two until I really see the viral load drop off.

While sometimes it’s easier just not to know, my family and I are happier knowing that we’re not unnecessarily spreading our viruses to eachother and others. I especially appreciate this extra protection from my family’s colds before going on a trip, nothing ruins a work trip or vacation more than getting a bad cold right at the start!

Tailoring tradeoffs to the virus

This past Christmas was particularly bad for respiratory infections in my house. First we had to cancel a plan to take our dads to the theater because I brought a Rhinovirus home from work and was still highly contagious. Then my son came home from University and immediately started feeling sick. I tested him right away and found that he had Influenza A. He immediately started isolating, and my wife and I avoided catching it but unfortunately my daugther was not so lucky. Her bedroom is next to his, I have since installed a UV-C sanitization lamp in their ductwork. We had a big party planned at our house with friends and Christmas dinners planned for both of our extended families. Needless to say, we were very sad about likely needing to cancel all of that to keep from sharing the Flu.

Luckily after only a few days, while still feeling terrible, both kids started to show only weak positive results on our antigen tests.

By Christmas Eve, after 5 days of my daughter being sick, and 8 days of my son being sick, they both still had pretty bad symptoms, coughing and blowing their noses. Normally we would have cancelled our Christmas plans, but the rapid tests were now completely negative. I ran PCR tests and they were both very weak positives (Cq of 33 and 34). I checked the academic literature and found that it was common for Influenza viral load to peak early in an infection and then drop off. We told our friends and family that our kids had the flu and were still sick, but had negative rapid tests and appeared to have low viral loads. Everyone agreed it was worth the risk to keep our plans. I put our heat exchanger on maximum circulation, cracked some windows and kept an eye on CO2 levels in the house. We ended up having a great party and two great family Christmas dinners (including my parents staying overnight). Best of all, we confirmed that nobody got sick afterwards!

I’m sure some people will disagree with our decision to put seniors at any risk of catching the flu. But the reality is that infection risk is everywhere, and it’s a normal human cognitive bias to be more afraid of risks we can easily quantify than risks we are ignorant of. Activities like Christmas shopping would probably be higher risk than visiting with my kids in a house with good ventilation was. I am sad to see how polarized society has become about infection risk as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (eg. attitudes on lockdowns). By understanding the data and reasoning rationally about risk-benefit tradeoffs, it seems clear to me that there is a huge pragmatic middle ground in the tradeoff space.

Leverage virus sub-typing

In order to know whether we are succeeding at keeping our colds from eachother, it’s useful to be able to differentiate different virus variants. For example, here’s a case where my Twitter followers predicted that I caught my son’s cold:

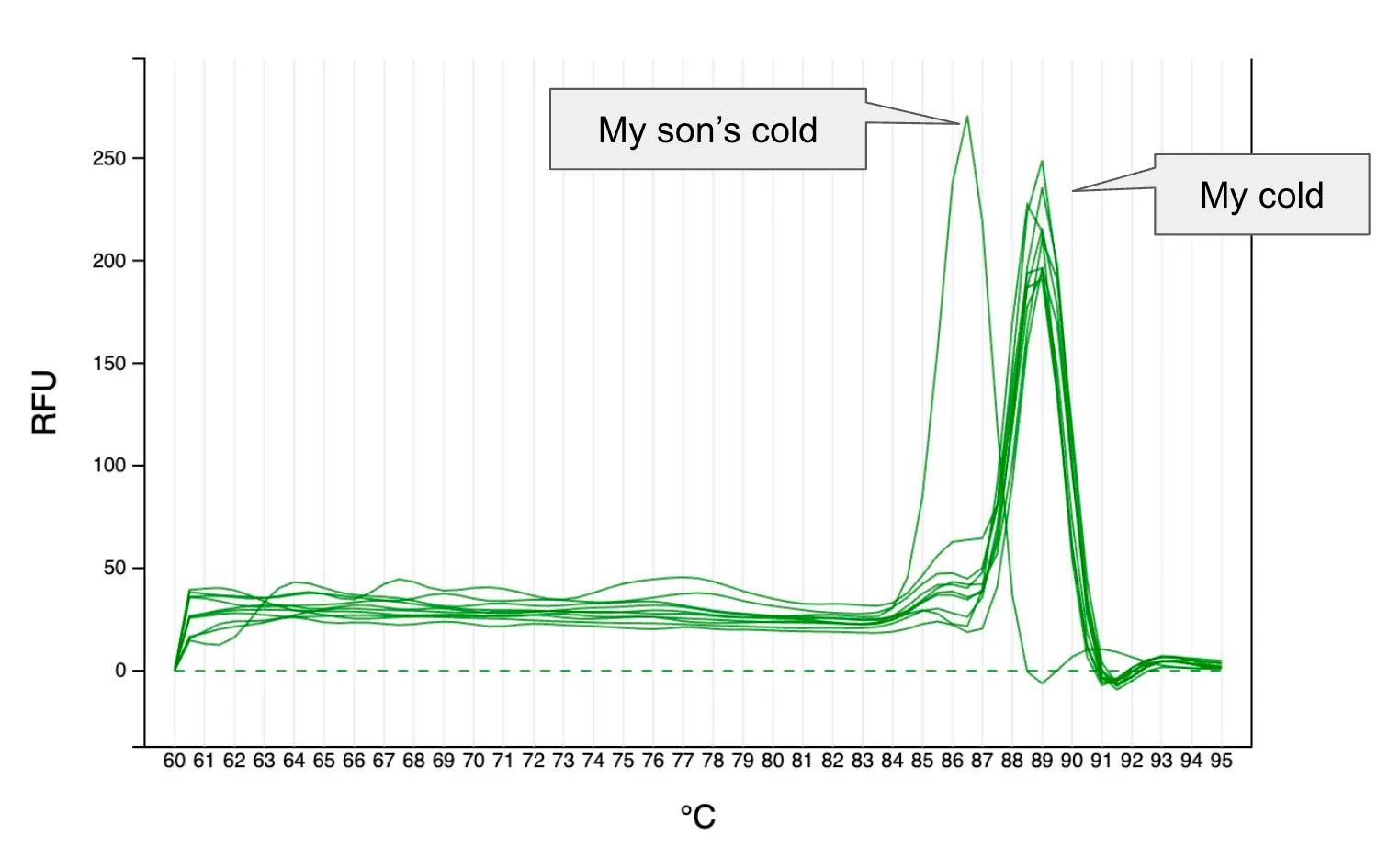

But I was able to do a quick and simple “melt analysis” which proved conclusively that they were different Rhinoviruses:

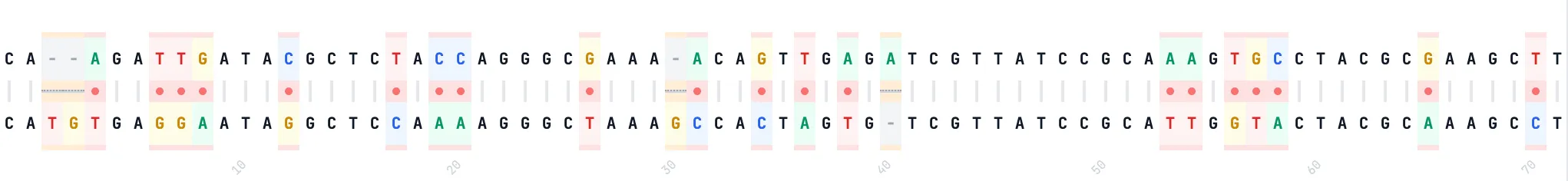

Later, when I had the time to run these viruses on my DNA sequencer, I was able to confirm that my son had a strain known as Rhinovirus A54, while I had a strain from a completely different species known as Rhinovirus C45. While both are Rhinoviruses, they are actually quite different from eachother, with only 77% of the bases matching in the short 350bp section I sequenced. This also meant that, while having just recovered from a cold, my son was probably not immune to my virus and so it was good that I isolated from him.

Supporting healthcare

Most doctors will say it’s not medically relevant to know which cold virus you have since the treatments are generally all the same. Nonetheless, I have found it occasionally useful.

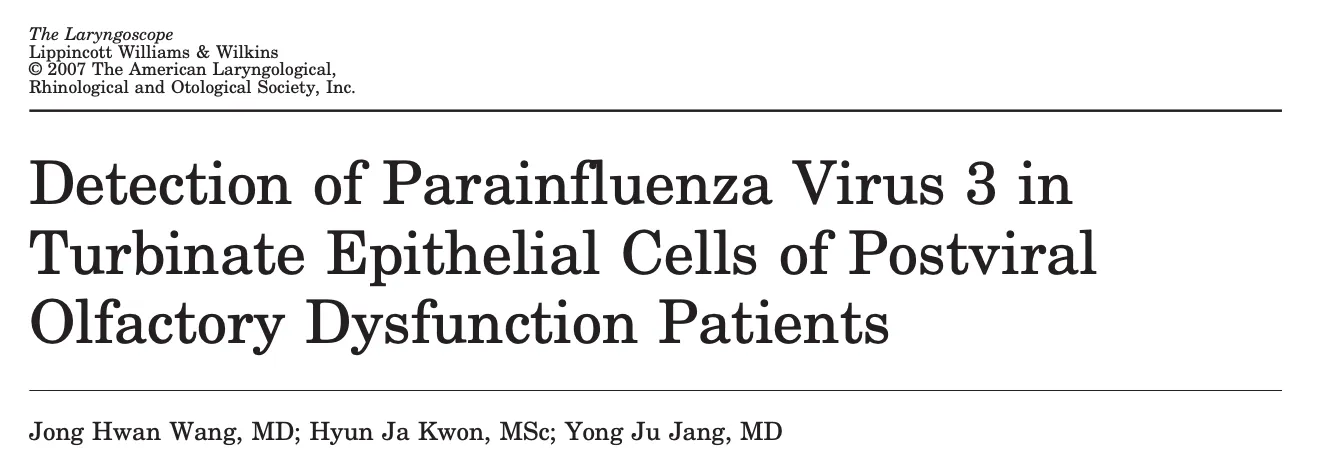

In July 2024 my family went on a European river cruise followed by a road trip. My wife and daughter caught a cold on the cruise, which my son and I got from them later in the trip. I lost my sense of smell and it mostly has not returned in the year and a half since. When I got home I found I had an unusual virus I’d never seen before “Parainfluenza 3”. Searching the academic literature for PIV-3 I discovered a paper indicating that it might be a hidden common cause of PVOD (post-viral lost of smell). I’ve had doctor and ENT specialist appointments and they always ask “do you know if it was COVID?”, and I’m glad to be able to say “no, it was PIV-3” and point them to this paper.

Contributing to vaccination strategy

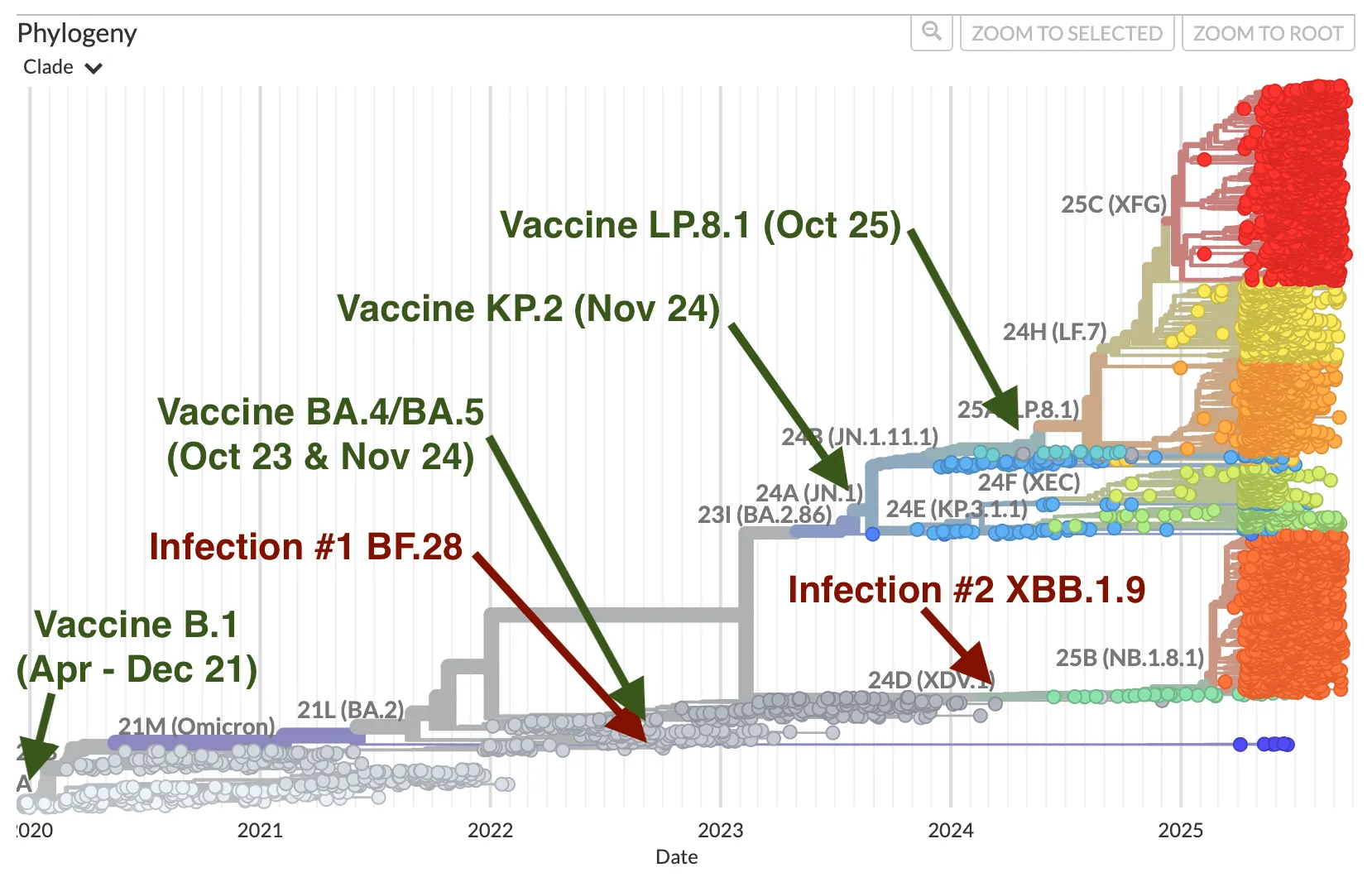

When deciding when to get an updated vaccine booster, it may sometimes be useful to know how similar the vaccine is to prior infections. For example in February 2024 I caught SARS-CoV-2 and from sequencing I knew it was the strain XBB.1.9, which was rare at the time. In November when I got the opportunity to get a booster shot, I found the vaccines were for a very different variant I hadn’t had yet, KP.2. If I had been on the fence on whether to bother with a booster (I was not), knowing that my natural immunity was so far removed from the popular variants and current vaccine would make an additional argument in favor of getting the booster.

Looking forward

If you’re still reading then I hope that means that, like me, you are fascinated by the idea of improving tools for understanding infections in our bodies. For now the best most people can do is to buy antigen tests for COVID, Flu and RSV. If you are lucky enough to have enough disposable income and live in a place where they are legally available, you could even buy a Pluslife or Metrix molecular test kit. Hopefully if enough people find these products useful, prices will come down further and more products will come to market which target more common pathogens like Rhinovirus. Perhaps it won’t be long before our toothbrushes come with cheap DNA sequencing for our whole mouth microbiome.

In the meantime, if you want to start learning molecular biology in your own home and can spare $1,000, I suggest buying a miniPCR and trying out one of their learning labs. You can also just follow me on BlueSky and I’ll try to keep you updated on how personal molecular virology is becoming closer to a pragmatic reality.